For generations, politics and parties were aligned largely along a horizontal axis between “left” and “right” ; this contrast has not disappeared, but it is now overlaid by a new axis between those who fundamentally favor open societies, trade, globalization, and multilateralism and others who demand closed borders, protectionism, bans on migration and unilateralism à la “My Country First”

Andreas Kluth

Alice Weidel is a fascinating woman, which is why we profiled her on September 20 under this headline: “Cosmopolitan Lesbian Turns Far-Right Agitator”. Four days later, she stood triumphant in Germany’s election, when the populist party she leads, called Alternative for Germany (AfD), became the third-strongest bloc in the Bundestag with almost 13 percent of the vote. The AfD is anti-immigrant, nationalist and homophobic. Ms. Weidel speaks Chinese and is raising two boys with her partner, a woman originally from Sri Lanka. The incongruence is a good story.

Alexander Gauland e Alice Weidel

But one word in our title caused offence, and it was not “lesbian”. An American woman named Fortune Rebecca Buchholtz had this to say on our Facebook page: “Please edit this headline because we all know what ‘cosmopolitan’ means…” Another commenter, Jason Lee, replied: “Wait, what do you think ‘cosmopolitan’ means?” Ms. Buchholtz elaborated: “It’s a slur that’s been used against ‘rootless Jews’ since the Protocols of Zion. It’s a common phrase from the ‘blood & soil’ far-right textbook…”

Ms. Buchholtz put her finger on a big subject. Indirectly, it explains the political shifts across Western societies, which have now — after some delay — reached even Germany. For generations, politics and parties in Europe and North America were aligned largely along a horizontal axis between “left” and “right” (the terms date to a seating arrangement during the French Revolution). This contrast has not disappeared. But it is now overlaid by a new axis between those who fundamentally favor open societies, trade, globalization, and multilateralism and others who demand closed borders, protectionism, bans on migration and unilateralism à la “My Country First”. And nothing distills this new confrontation more than the word “cosmopolitanism”.

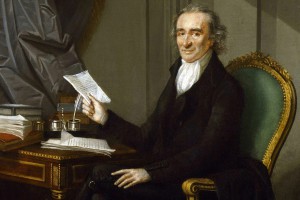

Thomas Paine

The first person on record for using the word was Diogenes, a Greek during the fourth century B.C.E. who lived in a barrel, half naked and “dog-like” (kynikos), and thus “cynical” in the original sense. Asked where he was from, he replied: “I am a kosmopolitês”, a citizen (politês) of the world (kosmo). Cosmopolitanism was thus born out of a radical yearning for freedom and a sense that all people, no matter their tribe, are really part of one community. Thomas Paine, an American revolutionary of the Enlightenment, expressed it best: “The world is my country; all mankind are my brethren, and to do good is my religion.”

But throughout the centuries, cosmopolitanism also had a distinct whiff of elitism. In Europe it was aristocrats who were cosmopolitan, or Hanseatic merchants (i.e. capitalists), or — at least in the popular imagination — Jews. To ordinary people, being a citizen of the world meant being a citizen of nowhere in particular. To some people ‘cosmopolitan’ even suggested being unmoored, uprooted, “footloose” (as in: capital), and thus disloyal, untrustworthy, subversive. Joseph Stalin used “cosmopolitanism” as his bogeyman for his purges of intellectuals, who were often Jewish.

The ultimate negation of cosmopolitanism was of course Nazism, an extreme nationalism that extolled, as Ms. Buchholtz pointed out, “blood and soil” until it became, in effect, “Aryans first, others dead.” This is why the Federal Republic of Germany (which long meant West Germany) defined itself in the exact opposite way: as an open and inclusive trading nation in a united Europe. Because of its past nationalist disease, this new Germany was deemed inoculated against a recurrence of the virus. Every attempt by right-wingers to form a viable political party failed, even long after most other European countries already had populists in their parliaments.

But the elites in Germany, like those in other European countries and in North America, underestimated the degree to which they, like the aristocrats and philosophers of yore, were losing touch with ordinary folk. Most people do not hate foreigners at all. And yet they yearn to belong to a community and to preserve it. In 2004, the late Samuel Huntington raised an alarm about this misunderstanding by the elites in his essay “Dead Souls: The Denationalization of the American Elite.”

Walter Scott

The difference “between the public and the elites is not isolationism versus internationalism, but nationalism versus cosmopolitanism,” he argued, and drove his point like a stake into our (elitist) hearts by quoting Walter Scott (1804):

Breathes there the man so dead

Who never to himself hath said:

“This is my own, my native Land?”

Whose heart hath ne’er within him burned

As home his footsteps he has turned,…

From wandering on a foreign strand?

If anybody had a premonition of the backlash that has now arrived, it was therefore Huntington. He died in 2008, just after the election of Barack Obama, a cosmopolitan with a Kenyan father and an Indonesian-Hawaiian childhood. Here we are nine years later: with Donald Trump in the White House, an “America First” president whose base includes white nationalists who are mad as heck about cosmopolitan elites. The same backlash has played out in Brexit Britain and is raging in Poland, Hungary, Turkey, Russia and elsewhere. Nationalists don’t always win — they recently suffered defeats in Austria, the Netherlands, and France. But they have mobilized.

That brings us back to Germany, allegedly the exception in this trend of re-nationalization, for the well-known historical reasons. But it turns out that even Germans had hearts that burned for their own, their native land, and secretly felt that their elites had dead souls. In one region, moreover, this longing combined with another ingredient that made it dangerous.

Like poor, white Americans in Appalachia or working-class Brits in northern England, Germans in the former East fear that they have been ignored and disrespected by their elites. Rationally or not, they feel that reunification made them second-class citizens in their own land. When new arrivals (refugees, in this case) showed up in huge numbers, and the elites appeared more empathetic with the newcomers, they blew their top. The result is the AfD. It is roughly twice as strong in what used to be East Germany as in the former West Germany. It came in first among East German men. In one eastern state, Saxony, it came in first overall.

In a few days, the AfD will take its 94 seats in the Bundestag. This is a historic event. But it is not one to panic about just yet, as I have argued before. The AfD represents people who were there all along, but so far silent. The AfD will now make their views audible and visible. If the party moderates over time, it can earn a place in the firmament of German democracy. If it becomes more extreme, Germans must and will reject it and consign the party to the trash heap of postwar German history where it can compost with all the other far-right movements that have failed in the past seven decades.

No matter the fate of this one party, the primary political dialectic of our time is now defined and here to stay. Open or closed, cosmopolitan or nationalist: where on this spectrum will countries — and individuals — find themselves? Incidentally, Ms. Buchholtz, as much as you made us think, we didn’t change the headline, and won’t stop using the word. We’re not dead souls, and we’re not elitists. But we’re proudly cosmopolitan, and we get to define what that word means.